BY MADI KHADIM

February 16, 2022

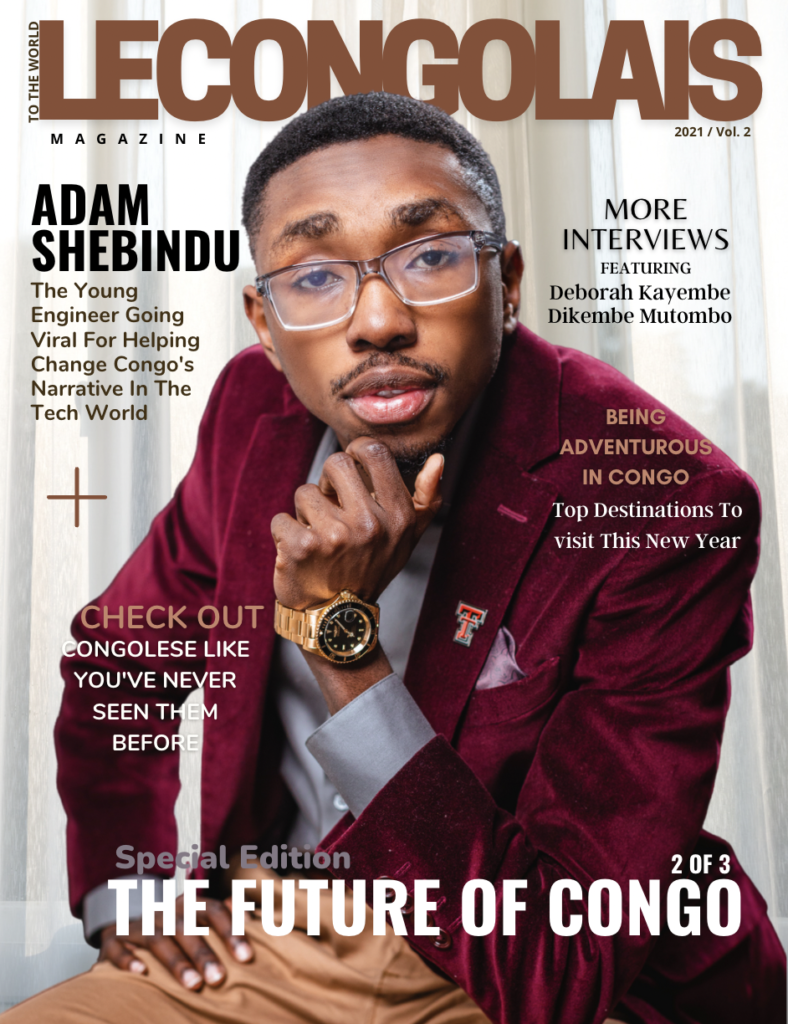

Aerial view of Lake Kivu © Shutterstock

Lake Kivu is a weird body of water in Africa. It is an exciting subject for scientists, as well as a major source of peril and fortune for the millions of people who live nearby due to its odd collection of qualities.

Kivu behaves differently than most deep lakes.

When water at the surface of a lake is cooled — for example, by winter air temperatures or rivers delivering spring snowmelt — the cold, dense water sinks, and warmer, less dense water rises from deeper inside the lake. Convection is a natural phenomenon that keeps the surface of deep lakes warmer than the depths.

Kivu is one of a number of lakes lining the East African Rift Valley, where tectonic forces are progressively pulling the African continent apart. It lies on the boundary between Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The ensuing forces cause the Earth’s crust to erode and volcanic activity to erupt, resulting in hot springs beneath Kivu that feed hot water, carbon dioxide, and methane into the lake’s bottom layers.

The “Under Pressure”

Only a few lakes on the planet are thought to be capable of limnic eruptions, with Lake Kivu being the largest. Thousands of kilometers west, two much smaller comparable lakes are located in Cameroon and the other in Italy.

These lakes are all near tectonically active locations, where volcanic gases such as CO2 rise from deep within the Earth. Seasonal temperature changes do not mix the waters from top to bottom since the lakes are deep. Instead, the dissolved gas condenses in the denser lower layers, which are subsequently sealed by a ‘cork’ of pressure from the upper layers. If the gasses build up to the point that bubbles form, these lakes can erupt like a champagne bottle.

The Mystery of Gas

Despite the potential danger that Kivu poses, there is much disagreement about the basics, such as the source of the gasses, whether they are rising, and if Lake Kivu has ever erupted. Despite the presence of nine dark layers in the sediments indicating mixing episodes in the last 2,000 years, analysts have found no proof of any violent events that might be classified as limnic eruptions in the last 12,000 years. Others, based on evidence, believe there was at least one eruption 4,000 years ago.

Many people may be surprised by the amount of life in such a seemingly lethal lake. The lake’s surface waters are crystal clear and teeming with fish.

Danger lurks at every corner

Lake Nyos, a crater lake in Cameroon some 1,400 miles northwest of Kivu, collects and traps massive concentrations of dissolved gas — in this case, carbon dioxide — from a volcanic vent at the lake’s bottom. On August 21, 1986, the gas reservoir’s fatal potential was spectacularly proven. When a movement in the water body occurred, it resulted in the release of carbon dioxide into the air. Around 1,800 people in adjacent villages were asphyxiated by a massive, lethal cloud of gas.

Limnic eruptions are comparable to this, and scientists think that Kivu is primed for a similar, much more deadly occurrence. Nyos is a smaller lake than Kivu, but Katsev claims that because of its size, Kivu “has the potential for a large, catastrophic limnic eruption releasing many cubic miles of gas.”

Exploration of the depths

The risk increases when gas concentrations in Kivu’s depths rise. Wüest and colleagues discovered that carbon dioxide concentrations rose 10% from 1974 to 2004, but methane concentrations surged 15 to 20% during the same time period, posing a greater threat at Kivu.

However, there may be a way to transform Kivu’s danger into profit. The same gas that could cause a devastating natural disaster could also be used as a renewable energy source in the area. Rwanda began a pilot program to extract methane from the lake and use it as natural gas in 2008 and signed a contract to export bottled methane last year. KivuWatt, a considerably larger program, was launched in 2015.

Methane Extraction

People have been sourcing methane from Lake Kivu on a small scale for decades in order to use it as an energy source. However, when KivuWatt, a London-based firm, started in 2016, the effort was greatly increased. The $200 million project now generates 26 megawatts (MW), with plans to expand to 100 MW in the future. Rwanda’s installed grid capacity, which is currently 200 MW, will be greatly increased.

KivuWatt’s withdrawals are now negligible in comparison to the lake’s stock: at current extraction rates, the company will remove less than 5% of the lake’s methane in 25 years. They must accelerate gas extraction to truly lower the risk of limnic eruption. However, supply and demand are the most important factors to consider.

The Advantages of Degassing

KivuWatt provides 2.5 million Rwandans (about 20% of the country’s population) with renewable base-load electricity. The project will lessen the dangers associated with CH4 and CO2 emission from the lake while simultaneously providing a long-term and ecologically friendly power supply. It would assist the government in fulfilling its target of 563 MW of installed power capacity by 2017, as well as lessen the country’s reliance on fuel for energy generation.

As of 2011, Rwanda had a 9% electricity rate and 68.4 MW of installed power capacity. Thirty communal power systems will get energy from the KivuWatt initiative. There will be around 200 manufacturing jobs and 60 long-term jobs generated.

However, the dispute over the safety of gas extraction continues. However, monitoring if and how the density strata change is the only way to settle the debate regarding how these operations may affect the lake.

The monetary value of Lake Kivu, its potential explosive capability, and the diverse range of options for dealing with it continue to elicit emotionally intense debates among stakeholders. While removing gas from the lake should make it safer, some things, such as a volcanic explosion, are beyond the control of any scientist, corporate, or regulatory authority.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.